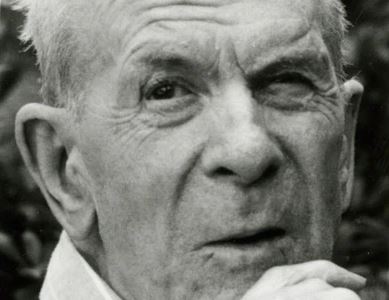

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross (1968)

“The Lamp at Noon” is a famous short story by Sinclair Ross. Sinclair Ross is one of Canada’s best-known prairie realists and “The Lamp at Noon” portrays a breakdown in communication. Paul is a farmer who refuses to give up despite years of drought and his wife Ellen feels trapped in their house and vulnerable to nature’s fury. When she can no longer cope with the failure and isolation, the story talks about her attempts to tell Paul what she is feeling and the story talks about the depths of her despair and the consequences.

You can download a free PDF copy of “The Lamp at Noon” by Sinclair Ross, right below. You can also download a PDF worksheet as well as the complete analysis below.

Table of contents – The Lamp at Noon

- Full Text – The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross

- Plot, Summary and Analysis – The Lamp at Noon

- Questions and Answers – The Lamp at Noon

- The Lamp at Noon – Worksheets PDF

- The Lamp at Noon – PDF

Other famous short stories

- The steadfast tin soldier

- Lamb to the slaughter

- The little match girl

- The goblin and the grocers

- The handsomest drowned man in the world

- The princess and the pea

The Lamp at Noon Short story by Sinclair Ross – Full Text

A little before noon she lit the lamp. Demented wind fled keening past the house: a wail through the eaves that died every minute or two. Three days now without respite it had held. The dust was thickening to an impenetrable fog. She lit the lamp, then for a long time stood at the window motionless. in dim, fitful outline the stable and oat granary still were visible; beyond, obscuring fields and landmarks, the lower of dust clouds made the farmyard seem an isolated acre, poised aloft above a sombre void. At each blast of wind it shook, as if to topple and spin hurtling with the dust-reel into space.

From the window she went to the door, opening it a little, and peering toward the stable again. He was not coming yet. As she watched there was a sudden rift overhead, and for a moment through th0e tattered clouds the sun raced like a wizened orange. It shed a soft, diffused light, dim and yellow as if it were the light from the lamp reaching out through the open door.

She closed the door, and going to the stove tried the potatoes with a fork. Her eyes all the while were fixed and wide with a curious immobility. It was the window. Standing at it, she had let her forehead press against the pane until eyes were strained apart and rigid. Wide like that they had looked out to the deepening ruin of the storm. Now she could not close them.

The baby started to cry. He was lying in a homemade crib over which she had arranged a tent of muslin. Careful not to disturb the folds of it, she knelt and tried to still him, whispering huskily in a singsong voice that he must hush and go to sleep again. She would have liked to rock him, to feel the comfort of his little body in her arms, but a fear had obsessed her that in the dust-filled air he might contract pneumonia. There was dust sifting everywhere. Her own throat was parched with it. The table had been set less than ten minutes, and already a film was gathering on the dishes. The little cry continued, and with wincing, frightened lips she glanced around as if to find a corner where the air was less oppressive. But while the lips winced the eyes maintained their

wide, immobile stare.

“Sleep,” she whispered again. “It’s too soon for you to be hungry. Daddy’s coming for his dinner.”

He seemed a long time. Even the clock, still a few minutes off noon, could no dispel a foreboding sense that he was longer than he should be. She went to the door again – and then recoiled slowly to stand white and breathless in the middle of the room. She mustn’t. He would only despise her if she ran to the stable looking for him. There was too much grim endurance in his nature ever to let him understand the fear and weakness of a woman. She must stay quiet and wait. Nothing was wrong. At noon he would come – and perhaps after dinner stay with her awhile.

Yesterday, and again at breakfast this morning, they had quarreled bitterly. She wanted him now, the assurance of his strength and nearness, but he would stand aloof, wary,

remembering the words she had flung at him in her anger, unable to understand it was only the dust and wing that had driven her.

Tense, she fixed her eyes upon the clock, listening. There were two winds: the wing in flight, and the wind that pursued. The one sought refuge in the eaves, whimpering, in fear; the other assailed it there, and shook the eaves apart to make it flee again. once as she listened this first wind spring inside the room, distraught like a bird that has felt the graze of talons on its wing; while furious the other wing shook the walls, and thudded tumbleweeds against the window till its quarry glanced away again in fright. But only to return – to return and quake among the feeble eaves, as if in all this dust0mad wilderness it knew no other sanctuary.

Then Paul came. At his step she hurried to the stove, intent upon the pots and fryingpan. “The worst wind yet” he ventured, hanging up his cap and smock. “I had to light the lantern in the tool shed, too.”

They looked at each other, then away. She wanted to go to him, to feel his arms supporting her, to cry a little just that he might soothe her, but because his presence made the menace of the wind seem less, she gripped herself and thought, “I’m in the right. I won’t give in. For his sake, too, I won’t.”

He washed, hurriedly, so that a few dark welts of dust remained to indent upon his face a haggard strength. It was all she could see as she wiped the dishes and set the good before him: the strength, the grimness, the young Paul growing old and hard, buckled against a desert even grimmer than his will. “Hungry?” she asked, touched to a twinge of pity she had not intended.

“There’s dust in everything. It keeps coming fast than I can clean it up.”

He nodded. “Tonight, though, you’ll see it go down. This is the third day.”

She looked at him in silence a moment, and then as if to herself muttered broodingly, “Until the next time. Until it starts again.”

There was a dark resentment in her voice now that boded another quarrel. He waited, his eyes on her dubiously as she mashed a potato with her fork. The lamp between them threw strong lights and shadows on their faces. Dust and drought, earth that betrayed alike his labour and his faith, to him the struggle had given sternness, an impassive courage. Beneath the whip of sand his youth had been effaced.

Youth, zest, exuberance – there remained only a harsh and clenched virility that yet became him, that seemed at the cost of more engaging qualities to be fulfillment of his inmost and essential nature. Whereas to her the same debts and poverty had brought a plaintive indignation, a nervous dread of what was still to come. The eyes were hollowed, the lips punched dry and colourless. It was the face of a woman that had aged without maturing, that had loved the little vanities of life, and lost them wistfully.

“I’m afraid, Paul,” she said suddenly. “I can’t stand it any longer. He cries all the time. You will go Paul – say you will. We aren’t living here – not really living -”

The pleading in her voice now, after its shrill bitterness yesterday, made him think that this was only another way to persuade him. He answered evenly, “I told you this morning, Ellen; we keep on right where we are. At least I do. It’s yourself you’re thinking about, not the baby.”

This morning such an accusation would have stung her to rage; now, her voice swift and panting, she pressed on, “Listen, Paul – I’m thinking of all of us – you, too. Look at the sky – what’s happening. Are you blind? Thistles and tumbleweeds – it’s a desert. You won’t have a straw this fall. You won’t be able to feed a cow or a chicken. Please, Paul, say we’ll go away -”

“Go where?” His voice as he answered was still remote and even, inflexibly in unison with the narrowed eyes and the great bunch of muscle-knotted shoulder. “Even as a desert it’s better than sweeping out your father’s store and running his errands. That’s all I’ve got ahead of me if I do what you want.”

“And here -” she faltered. “What’s ahead of you here? At least we’ll get enough to eat and wear when you’re sweeping out his store. Look at it – look at it, you fool. Desert – the lamp lit at noon -”

“You’ll see it come back. There’s good wheat in it yet.”

“But in the meantime – year after year – can’t you understand, Paul? We’ll never get them back -”

He put down his knife and fork and leaned toward her across the table. “I can’t go, Ellen. Living off you’re people – charity – stop and think of it. This is where I belong. I can’t do anything else.”

“Charity!” she repeated him, letting her voice rise in derision.

“And this – you call this independence! Borrowed money you can’t even pay the interest on, seed from the government – grocery bills – doctor bills -”

“We’ll have crops again,” he persisted. “Good crops – the land will come back. It’s worth waiting for.”

“And while we’re waiting, Paul!” It was not anger now, but a kind of sob. “Think of me – and him. It’s not fair. We have our live, too, to live.”

“And you think that going home to your family – taking your husband with you -”

“I don’t care – anything would be better than this. Look at the air he’s breathing. He cries all the time. For his sake, Paul. What’s ahead of him here, even if you do get crops?”

He clenched his lips a minute, then, with his eyes hard and contemptuous, struck back, “As much as in town, growing up a pauper. You’re the one who wants to go, it’s not for his sake. You think that in town you’d have a better time – not so much work – more clothes -”

“Maybe -” She dropped her head defenselessly. “I’m young still. I like pretty things.”

There was a silence now – a deep fastness of it enclosed by rushing wind and creaking walls. It seemed the yellow lamplight cast a hush upon them. Through the haze of dusty air the walls receded, dimmed, and came again. At last she raised her head and said listlessly, “Go on – your dinner’s getting cold. Don’t sit and stare at me. I’ve said it all.”

The spend quietness was even harder to endure than her anger. It reproached him, against his will insisted that he see and understand her lot. To justify himself he tried, “I was a poor man when you married me. You said you didn’t mind. Farming’s never been easy, and never will be.”

“I wouldn’t mind the work or the skimping if there was something to look forward to. It’s the hopelessness – going on – watching the land blow away.”

“The land’s all right,” he repeated. “The dry years won’t last forever.”

“But it’s not just dry years, Paul!” The little sob in her voice gave way suddenly to a ring of exasperation. “Will you never see? It’s the land itself – the soil. You’ve plowed and harrowed it until there’s not a root or fibre left to hold it down. That’s why the soil drifts – that’s why in a year or two there’ll be nothing left but the bare clay. If in the first place you farmers had taken care of your land – if you hadn’t been so greedy for wheat every year -”

She had taught school before she married him, and of late in her anger there had been a kind of disdain, an attitude almost of condescension, as if she no longer looked upon the farmers as her equals. He sat still, his eyes fixed on the yellow lamp flame, and seeming to know how her words had hurt him, she went on softly, “I want to help you, Paul. That’s why I won’t sit quiet while you go on wasting your life. You’re only thirty – you owe it to yourself as well as me.”

He sat staring at the lamp without answering, his mouth sullen. It seemed indifference now, as if he were ignoring her, and stung to anger again she cried, “Do you ever think what my life is? Two rooms to live in – once a month to town, and nothing to spend when I get there. I’m still young – I wasn’t brought up this way.”

“You’re a farmer’s wife now. It doesn’t matter what you used to be, or how you were brought up. You get enough to eat and wear. Just now that’s all I can do. I’m not to blame that we’ve been dried out five years.”

“Enough to eat!” she laughed back shrilly.

“Enough salty pork – enough potatoes and eggs. And look -” Springing to the middle of the room she thrust out a foot for him to see the scuffed old slipper. “When they’re completely gone I suppose you’ll tell me I can go barefoot – that I’m a farmer’s wife – that it’s not your fault we’re dried out -”

“And what about these?” He pushed his chair away from the table now to let her see what he was wearing. “Cowhide – hard as boards – but my feet are so calloused I don’t feel them anymore.”

Then he stood up, ashamed of having tried to match her hardships with his own. But frightened now as he reached for his smock she pressed close to him. “Don’t go yet. I brood and worry when I’m left alone. Please, Paul – you can’t work on the land anyway.”

“And keep on like this? You start before I’m through the door. Week in and week out – I’ve trouble enough of my own.”

“Paul – please stay -” The eyes were glazed now, distended a little as if with the intensity of her dread and pleading. “We won’t quarrel any more. Hear it! I can’t work – just stand still and listen -”

The eyes frightened him, but responding to a kind of instinct that he must withstand her, that it was his self-respect and manhood against the fretful weakness of a woman, he answered unfeelingly, “In here sage and quiet – you don’t know how well off you are. If you were out in it – fighting it – swallowing it -”

“Sometimes, Paul, I wish I was. I’m so caged – if I could only break away and run. See – I stand like this all day. I can’t relax. My throat’s so tight it aches -” With a jerk he freed his smock from her clutch. “If I stay we’ll only keep on all afternoon. Wait till tomorrow – we’ll talk things over when the wind goes down.”

Then without meeting her eyes again he swung outside, and doubled low against the buffets of the wind, fought his way slowly toward the stable. There was a deep hollow calm within, a vast darkness engulfed beneath the tides of moaning wind. He stood breathless a moment, hushed almost to a stupor by the sudden extinction of the storm and the stillness that enfolded him. It was a long, far-reaching stillness. The first dim stalls and rafters led the way into cavern-like obscurity, into vaults and recesses that extended far beyond the stable walls. Nor in these first quiet moments did he forbid the illusion, the sense of release from a harsh, familiar world into one of peace and darkness.

The contentious mood that his stand against Ellen had roused him to, his tenacity and clenched despair before the ravages of wind, it was ebbing now, losing itself in the cover of darkness. Ellen and the wheat seemed remote, unimportant. At a whinny from the bay mare, Bess, he went forward and into her stall. She seemed grateful for his presence, and thrust her nose deep between his arm and body. They stood a long time motionless, comforting and assuring each other.

For soon again the first deep sense of quiet and peace was shrunken to the battered shelter of the stable. Instead of release from the assaulting wind, the walls were but a feeble stand against it. They creaked and sawed as if the fingers of a giant hand were tightening to collapse them; the empty loft sustained a pipelike cry that rose and fell but never ended. He saw the dust-black sky again, and his fields blown smooth drifted soil.

But always, even while listening to the storm outside, he could feel the tense and apprehensive stillness of the stable. There was not a hoof that clumped or shifted, not a rub of halter against manger. And yet, though it had been a strange stable, he would have known, despite the darkness, that every stall was filled. They, too, were all listening.

From Bess he went to the big grey gelding, Prince. Prince was twenty years old, with rib-grooved sides, and high, protruding hipbones. Paul ran his hand over the ribs, and felt a sudden shame, a sting of fear that Ellen might be right in what she said. For wasn’t it true – nine years a farmer now on his own land, and still he couldn’t even feed his horses? What, then, could he hope to do for his wife and son?

There was much he planned. And so vivid was the future of his planning, so real and constant, that often the actual present was but half felt, but half endured. Its difficulties were lessened by a confidence in what lay beyond them. A new house – land for the boy – land and still more land – or education, whatever he might want.

But all the time was he only a blind and stubborn fool? Was Ellen right? Was he trampling on her life, and throwing away his own? The five years since he married her, were they to go on repeating themselves, five, ten, twenty, until all the brave future he looked forward to was but a stark and futile past?

She looked forward to no future. She had no faith or dream with which to make the dust and poverty less real. He understood suddenly. He saw her face again as only a few minutes ago it had begged him not to leave her. The darkness round him no was as a slate on which her lonely terror limned itself. He went from Prince to the other horses, combing their manes and forelocks with his fingers, but always it was he face before him, its staring eyes and twisted suffering. ‘See Paul – I stand like this all day. I just stand still – My throat’s so tight it aches -”

And always the wind, the creak of walls, the wild lipless wailing through the loft. Until at last as he stood there, staring into the livid face before him, it seemed that this scream of wind was a cry from her parched and frantic lips. He knew it couldn’t be, he knew that she was safe within the house, but still the wind persisted as a woman’s cry. The cry of a woman with eyes like those that watched him through the dark. Eyes that were mad now – lips that even as they cried still pleaded, “See Paul – I stand like this all day. I just stand still – so caged! If I could only run!”

He saw her running, pulled and driven headlong by the wind, but when at last he returned to the house, compelled by his anxiety, she was walking quietly back and forth with the baby in her arms. Careful, despite his concern, not to reveal a fear or weakness that she might think capitulation to her wishes, he watched a moment through the window, and then went off to the tool shed to mend harness. All afternoon he stitched and riveted. It was easier with the lantern lit and his hands occupied.

There was a wing whining high past the tool shed too, but it was only wind. He remembered the arguments with which Ellen had tried to persuade him away from the farm, and one by one he defeated them. There would be rain again – next year or the next. Maybe in his ignorance he had farmed his land the wrong way, seeding wheat every year, working the soil till it was lifeless dust – but he would do better now. He would plant clover and alfalfa, breed cattle, acre by acre and year by year restore to his land its fibre and fertility. That was something to work for, a way to prove himself. It was ruthless wind, blackening the sky with his earth, but it was not his master.

Out of his land it had made a wilderness. He now, out of the wilderness, would make a farm and home again. Tonight he must talk with Ellen. Patiently, when the wind was down, and they were both quiet again. It was she who had told him to grow fibrous crops, who had called him an ignorant fool because he kept on with summer fallow and wheat. Now she might be gratified to find him acknowledging her wisdom. Perhaps she would begin to feel the power and steadfastness of the land, to take pride in it, to understand that he was not a fool, but working for her future and their son’s.

And already the wind was slackening. At four o’clock he could sense a lull. At five, straining his eyes from the tool shed doorway, he could make out a neighbour’s buildings half a mile away. It was over – three days of blight and havoc like a scourge – three days so bitter and so long that for a moment he stood still, unseeing, his sense idle with a numbness of relief.

But only for a moment. Suddenly he emerged from the numbness; suddenly the fields before him struck his eyes to comprehension. They lay black, naked. Beaten and mounded smooth with dust as if a sea in gentle swell had turned to stone. And though he had known since yesterday that not a blade would last the storm, still now, before the utter waste confronting him, he sickened and stood cold. Suddenly like the fields he was naked. Everything that had sheathed him a little from the realities of existence: vision and purpose, faith in the land, in the future, in himself – it was all rent now, stripped away.

“Desert,” he heart her voice begin to sob. “Desert, you fool – the lamp lit at noon!”

In the stable again, measuring out their feed to the horses, he wondered what he would say to her tonight. For so deep were his instincts of loyalty to the land that still, even with the images of his betrayal stark upon his mind, his concern was how to withstand her, how to go on again and justify himself. It had not occurred to him yet that he might or should abandon the land. He had lived with it too long. Rather was his impulse still to defend it – as a man defends against the scorn of stranger even his most worthless kin.

He fed his horses, then waited. She too would be waiting, ready to cry at him, “Look now – that crop that was to feed and clothe us! And you’ll keep on! You’ll still say ‘Next year – there’ll be rain next year’!”

But she was gone when he reached the house. The door was open, the lamp blown out, the crib empty. The dishes from the meal at noon were still on the table. She had perhaps begun to sweep, for the broom was lying in the middle of the floor. He tried to call, but a terror clamped upon his throat. In the wan, returning light it seemed that even the deserted kitchen was straining to whisper what it had seen. The tatters of the storm still whimpered through the eaves, and in their moaning told the desolation of the miles they had traversed. On tiptoe at last he crossed to the adjoining room; then at the threshold, without even a glance inside to satisfy himself that she was really gone, he wheeled again and plunged outside.

He ran a long time – distraught and headlong as a few hours ago he had seemed to watch her run – around the farmyard, a little distance into the pasture, back again blindly to the house to see whether she had returned – and then at a stumble down the road for help.

They joined him in the search, rode away for others, spread calling across the fields in the direction she might have been carried by the wind – but nearly two hours later it was himself who came upon her. Crouched down against a drift of sand as if for shelter, her hair in matted strands around her neck and face, the child clasped tightly in her arms.

The child was quite cold. It had been her arms, perhaps, too frantic to protect him, or the smother of dust upon his throat and lungs. “Hold him,” she said as he knelt beside her.

“So – with his face away from the wind. Hold him until I tidy my hair.”

Her eyes were still wide in an immobile stare, but with her lips she smiled at him. For a long time he knelt transfixed, trying to speak to her, touching fearfully with the fingertips the dust-grimed cheeks and eyelids of the child.

At last she said, “I’ll take him again. Such clumsy hands – you don’t know how to hold a baby yet. See how his head falls forward on your arm.”

Yet it all seemed familiar – a confirmation of what he had known since noon. He gave her the child, then, gathering them up in his arms, struggled to his feet, and turned toward home. It was evening now. Across the fields a few spent clouds of dust still shook and fled. Beyond, as if through smoke, the sunset smouldered like a distant fire. He walked with a long dull stride, his eyes before him, heedless of her weight. Once he glanced down and with her eyes she still was smiling.

“Such strong arms, Paul – and I was so tired just carrying him. . . .”

He tried to answer, but it seemed that now the dusk was drawn apart in breathless waiting, a finger on its lips until they passed.

“You were right, Paul. . . .” Her voice came whispering, as if she too could feel the hush. “You said tonight we’d see the storm go down. So still now, and a red sky – it means tomorrow will be fine.”

Questions and Answers – The Lamp at Noon – Set 1

- What is the short story The Lamp at Noon about?

- “The Lamp at Noon” by Sinclair Ross explores the psychologically devastating effects that the environmental devastation of the dust bowl has on the psyches and relationship of a married couple living on a farm on the Canadian plains during the Great Depression.

- What is the message of The Lamp at Noon?

- In the short story, “The Lamp at Noon,” the author Sinclair Ross develops the idea of the negative impact of isolation on individuals. The author suggests that isolation can cause an individual to feel emotionally detached and frustrated which may drive them to act irrationally.

- What does the lamp in The Lamp at Noon symbolize?

- Firstly, the land symbolizes the state of the main characters’ (Ellen and Paul) marriage. Next, the violent winds outside embody the conflict between Ellen and Paul. Finally, the lamp represents Ellen and Paul’s hope for a better future.

- What is the point of view of The Lamp at Noon?

- In the short story “The Lamp at Noon” It is a third person, omniscient point of view. The person reading the story is not directly involved with the characters in the story. We as the readers don’t know everything that is happening in the story, we only get to see one side of the story at a time.

- What happens at the end of The Lamp at Noon?

- At the end of the short story, Ellen and Paul had lost their baby son. This is when Paul realizes how his decisions affected the family and Ellen remained insane and in shock. Isolation is the complete separation of others.

Questions and Answers – The Lamp at Noon – Set 2

- What is the irony in The Lamp at Noon?

- Paul and Ellen used one lamp to guide them through the storm when they would definitely have more lights to use if this was as big a storm as described. Paul said that he did not want to depend on “Charity” in order to survive but he took out loans in order to make ends meet.

- What does the red sky symbolize in The Lamp at Noon?

- The reader is finally told by the author about Ellen’s change of perspective when she says is talking to Paul. She told him he was right, that the storm would go down, and a red sky, meaning that “tomorrow will be fine.”

- Is the ending of The Lamp at Noon optimistic or pessimistic?

- Hope was restored in Ellen for the small family’s crops to grow and for them to finally have rain. She realizes that living with pessimism wouldn’t help anything, so in the end this ending was optimistic.

- What is the foreshadowing in The Lamp at Noon?

- Ellen says, “I’m so caged – if I could only break away and run.” This foreshadowed Ellen later running away with the baby.

- What is the flashback in The Lamp at Noon?

- The drought and sandstorms lasted several years and Ellen wanted to leave but she couldn’t persuade him. – When Paul is in the stable thinking, he gets many flashbacks of what Ellen told him and they keep coming to him.

Questions and Answers – The Lamp at Noon – Set 3

- What are the two winds in The Lamp at Noon?

- There were two winds: the winds in flight, and the wind that pursued. The one sought refuge in the eaves, whimpering, in fear; the other assailed it there, and shook the eaves apart to make it flee again

- Why does Ellen finally run away in The Lamp at Noon?

- Ellen exclaims that she feels caged in and just wants to leave. The sand has been getting to her head and she is sick of it. At the end of the story Ellen is pushed past her breaking point and decides she is going to leave, just as she mentioned in this passage.

- What are the character traits of Ellen in The Lamp at Noon?

- Ellen is a farmer’s wife who is living in harsh conditions, and wants to escape the farm life and move to the city to build a better life for her and her child. Although Ellen is kind and thoughtful she displays acts of selfishness and impatience. Ellen is the protagonist in the story.

- What is the relationship between Ellen and Paul in The Lamp at Noon?

- In The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross, Paul and Ellen’s relationship is strained. They are mentally isolated from each other. Paul becomes accustomed to this isolation and does not sympathize with Ellen’s need for companionship and purpose.

Lamp at Noon – Character Sketches

In “The Lamp at Noon” by Sinclair Ross, there are two central characters: Ellen and Paul. Let’s delve into character sketches for each of them:

- Ellen:

- Desires and Dreams: Ellen is portrayed as a woman with dreams and desires beyond the harsh reality of the prairie farm. She yearns for a life with more connection, warmth, and emotional fulfillment. Her dreams are in stark contrast to the relentless toil and isolation imposed by their rural existence.

- Struggle with Isolation: Ellen grapples with the isolation imposed by the farm and the unforgiving prairie landscape. Her yearning for companionship and a life beyond the farm intensifies as the story progresses. The constant wind, symbolizing the emotional and physical isolation, takes a toll on her mental state.

- Emotional Turmoil: Throughout the narrative, Ellen experiences emotional turmoil due to the conflicting desires between her yearning for a different life and her commitment to the farm and marriage. The storm serves as a metaphor for the internal storms within her, reflecting the emotional turbulence she faces.

- Symbolism of the Lamp: Ellen’s plea for Paul to light the lamp is a desperate call for emotional connection and hope. The lamp represents her desire for a small yet significant source of warmth and light in the darkness of their existence.

- Paul:

- Stoicism and Practicality: Paul is depicted as a stoic farmer, resilient and determined to make a living from the challenging prairie land. His practicality and commitment to his work are evident in his efforts to endure the harsh conditions and provide for his family. However, this practicality sometimes blinds him to the emotional needs of his wife.

- Disconnect from Ellen: Despite his commitment to the farm, Paul becomes increasingly disconnected from Ellen’s emotional struggles. His focus on survival and providing for the family leads him to overlook the emotional toll their isolated life takes on Ellen. This disconnect becomes a source of tension in their relationship.

- Conflict with Nature: Paul’s character is also in conflict with the harsh nature of the prairie. His efforts to tame the land and make a living from it are a constant struggle against the relentless wind and barren landscape. This external conflict mirrors the internal conflict within their marriage.

- Reluctance and Resignation: In the climax, Paul reluctantly agrees to light the lamp for Ellen, symbolizing a temporary concession to her emotional needs. However, the story concludes with a sense of resignation, as the external forces of nature and circumstance overpower their attempts to find solace and connection.

Together, Ellen and Paul represent the emotional and psychological toll of rural isolation during the Great Depression. Their characters are intricately woven into the fabric of the prairie landscape, symbolizing the broader human experience of facing adversity, dreams clashing with reality, and the complex dynamics within relationships strained by external challenges.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Summary

“The Lamp at Noon” is a short story set during the Great Depression in the Canadian prairies. The narrative revolves around a married couple, Ellen and Paul, who live on a remote farm. The story explores the challenges they face as they struggle with the harsh conditions of the environment and the emotional strain on their relationship.

Ellen, yearning for a life beyond the isolation of the farm, pleads with Paul to light the lamp during a relentless and destructive windstorm. The lamp symbolizes her desire for connection and a small source of warmth in the darkness of their existence. Paul, initially resistant, eventually concedes to her request.

As the storm reaches its peak, the brief illumination from the lamp highlights the emotional turmoil within the characters. However, the light proves to be fleeting, and the story concludes with a sense of resignation and defeat. The external forces of nature and circumstance overwhelm the couple’s attempts to find solace, leaving them grappling with the challenges of rural life and the enduring impact of isolation.

The narrative skillfully portrays the conflict between individual aspirations and the harsh realities of the environment, using the symbolism of the lamp to underscore the characters’ emotional struggles. “The Lamp at Noon” is a poignant exploration of the human condition, capturing the essence of despair and the elusive pursuit of hope in the face of overwhelming odds.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Analysis

“The Lamp at Noon” is a short story written by Canadian author Sinclair Ross in 1968. Set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, the narrative unfolds in the harsh and unforgiving Canadian prairie landscape. The story revolves around the lives of a married couple, Ellen and Paul, as they grapple with the challenges of rural life and the emotional strain it puts on their relationship.

The title, “The Lamp at Noon,” carries symbolic weight, suggesting a beacon in the midst of darkness, a source of light and hope. In the story, the lamp becomes a metaphor for conflicting desires and aspirations, illuminating the struggles faced by the characters. Ross masterfully explores themes such as isolation, the impact of environmental conditions, and the tension between individual dreams and collective survival.

The setting is a critical element in the narrative, shaping the characters and influencing their decisions. The desolate prairie, marked by relentless winds and endless expanses of barren land, mirrors the emotional aridity within the characters’ lives. Ross vividly describes the physical environment, creating a sense of confinement and entrapment that amplifies the characters’ struggles.

Ellen and Paul represent the archetypal couple grappling with the challenges of rural life during the Depression era. Paul is portrayed as a stoic farmer determined to make a living from the unforgiving land. His commitment to his work is evident in his tireless efforts to tame the land and provide for his family. However, this dedication comes at a cost, as Paul becomes increasingly disconnected from his wife’s emotional needs.

Ellen, on the other hand, is depicted as a woman yearning for connection and a life beyond the confines of the farm. Her desire for a different, more fulfilling existence clashes with Paul’s practicality and insistence on persevering through the harsh conditions. The tension between their divergent aspirations forms the emotional core of the narrative.

The symbolism of the lamp takes center stage as Ellen, driven to the brink of despair by the relentless wind and isolation, pleads with Paul to light the lamp. The lamp, in this context, becomes a symbol of hope and connection, a small yet significant source of warmth and comfort in the midst of a desolate landscape. Ellen’s desperate plea for the light reflects her yearning for emotional illumination and a break from the pervasive darkness surrounding them.

The storm that envelops the farm serves as both a literal and metaphorical force in the story. As the wind intensifies, so does the emotional turmoil within the characters. The storm becomes a manifestation of the external pressures bearing down on them, mirroring the internal conflicts tearing at their relationship. The howling wind, which permeates every aspect of their lives, symbolizes the harsh realities of the environment and the emotional turbulence within the characters.

Ross skillfully employs the limited third-person point of view to provide insight into the thoughts and emotions of both Ellen and Paul. This narrative choice allows readers to empathize with the internal struggles of each character, enhancing the emotional impact of the story. The limited perspective also adds a layer of complexity to the narrative, as it becomes clear that neither character fully comprehends the depth of the other’s pain and desires.

The conclusion of the story is both poignant and tragic. As the storm reaches its peak, Paul reluctantly agrees to light the lamp for Ellen. However, the light it provides is fleeting, and the story closes with a sense of resignation and defeat. The lamp, while momentarily dispelling the darkness, cannot overcome the overwhelming forces of nature and circumstance. The ending leaves readers with a haunting sense of the fragility of human aspirations in the face of external challenges.

“The Lamp at Noon” is a powerful exploration of the human condition, capturing the essence of despair and the struggle for connection in the midst of adversity. Through its evocative prose and nuanced characters, Sinclair Ross crafts a timeless narrative that resonates with readers, inviting contemplation on the enduring themes of isolation, sacrifice, and the elusive pursuit of hope in the face of overwhelming odds.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Theme

“The Lamp at Noon” by Sinclair Ross explores several themes that resonate throughout the narrative, offering readers insight into the human condition and the challenges of rural life during the Great Depression. Some prominent themes include:

- Isolation:

- Physical and Emotional Isolation: The story vividly portrays the isolation experienced by the characters, Ellen and Paul, in their remote prairie farm. The vast, desolate landscape contributes to their physical isolation, while the emotional distance between the couple exacerbates their sense of loneliness. The relentless wind, a constant presence in the narrative, becomes a symbol of the isolating forces at play.

- Desperation and Despair:

- Economic Hardship: The Great Depression serves as the backdrop for the story, and the economic hardships of the era are reflected in the characters’ struggle to make a living from the harsh prairie land. The desperation brought about by financial difficulties adds to the overall sense of despair that permeates the narrative.

- Conflict between Dreams and Reality:

- Divergent Aspirations: Ellen and Paul embody the conflict between individual dreams and the harsh reality of their circumstances. Ellen yearns for a life beyond the farm, seeking emotional connection and fulfillment. In contrast, Paul is determined to persevere through the difficulties of rural life and fulfill his role as a provider. This internal conflict adds depth to the characters and highlights the broader theme of dreams clashing with reality.

- Nature as a Powerful Force:

- The Harsh Environment: The prairie landscape, with its relentless windstorms and barren expanses, is a formidable antagonist in the story. Nature is depicted as a powerful force that shapes the characters’ lives and decisions. The struggle to tame the land and withstand the elements becomes a metaphor for the broader human struggle against external challenges.

- Symbolism of the Lamp:

- Hope and Connection: The lamp serves as a powerful symbol throughout the narrative. Ellen’s plea for Paul to light the lamp represents her yearning for hope and emotional connection in the midst of their harsh and isolated existence. The lamp, albeit briefly, provides a small source of warmth and illumination in the darkness, symbolizing the fleeting nature of hope in the face of overwhelming challenges.

- Resignation and Defeat:

- The Inescapable Reality: The story concludes with a sense of resignation and defeat. Despite the characters’ brief attempt to find solace in the light of the lamp, the external forces of nature and circumstance overpower their efforts. The ending underscores the inescapable reality of their situation and the enduring impact of isolation on the human spirit.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Irony

“Irony” in literature often involves a contrast between expectations and reality, and “The Lamp at Noon” by Sinclair Ross employs irony to highlight the complexities and hardships faced by its characters. Here are instances of irony in the story:

- Title Significance:

- Irony in Hope: The title, “The Lamp at Noon,” suggests a source of light and hope in the midst of darkness. However, the irony lies in the fact that the lamp, while symbolizing hope for Ellen, provides only a momentary respite from the overwhelming challenges the characters face. The storm, both literal and metaphorical, intensifies despite the brief illumination.

- Nature as a Double-Edged Sword:

- The Wind’s Dual Nature: The relentless wind, a pervasive force in the narrative, is both symbolic and literal. While it symbolizes the emotional and physical isolation experienced by the characters, it also becomes a destructive force during the storm. The irony lies in the dual nature of the wind—representing both the characters’ internal struggles and the external threat to their farm.

- The Lamp as a Symbol:

- Temporary Illumination: The lamp, a symbol of hope and emotional connection, is lit at Ellen’s request during the storm. The irony emerges as the light it provides is fleeting, emphasizing the temporary nature of the solace it offers. Despite their attempt to find a brief respite from the darkness, the lamp fails to overcome the overwhelming forces of nature and circumstance.

- Conflict between Dreams and Reality:

- Unfulfilled Aspirations: The irony in the characters’ aspirations lies in the stark contrast between their dreams and the harsh reality of their lives. Ellen’s yearning for a different, more fulfilling life clashes with Paul’s commitment to the farm and survival. The irony is in the characters’ struggle to reconcile their individual aspirations with the challenging circumstances imposed by their environment.

- The Farm as a Symbol:

- The Farm’s Dual Role: The farm, initially a symbol of sustenance and survival, becomes ironic as it transforms into a source of emotional and psychological strain on the characters. While Paul sees the farm as a means of providing for his family, it also becomes a source of isolation and conflict, contributing to the overarching irony in the story.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Worksheet PDF

You can download a free PDF copy of The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross worksheet right below. This has a lot of questions and answers on this short story.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Worksheet

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Short story – Full Text – PDF

Are you looking for a free downloadable PDF copy of The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy of The Lamp at Noon Short story right below.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Short story – Full Text – PDF

The Lamp at Noon – Analysis – PDF

Are you looking for the analysis PDF copy of The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Analysis

The Lamp at Noon – Irony – PDF

Are you looking for the PDF copy of irony in The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Irony

The Lamp at Noon – Theme – PDF

Are you looking for the PDF copy of theme around The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.

The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross – Theme

The Lamp at Noon – Character Sketches – PDF

Are you looking for the PDF copy of character sketches of the titular characters of The Lamp at Noon by Sinclair Ross? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.