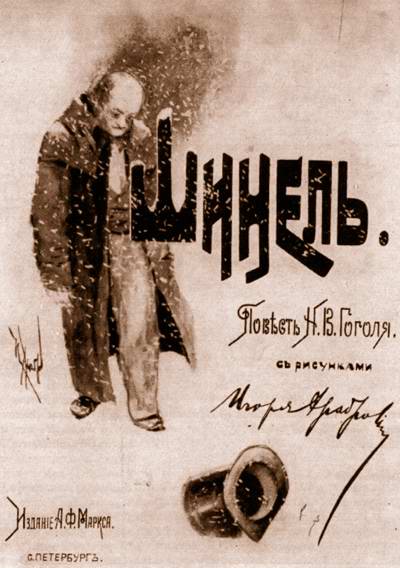

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol with PDF

Table of contents – The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol

- The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Full Text

- Plot, Summary and Analysis – The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol

- The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Full Text – PDF

- Analysis PDF

- Theme PDF

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Full Text

In the department of—but it is better not to mention the department. There is nothing more irritable than departments, regiments, courts of justice, and, in a word, every branch of public service. Each individual attached to them nowadays thinks all society insulted in his person. Quite recently a complaint was received from a justice of the peace, in which he plainly demonstrated that all the imperial institutions were going to the dogs, and that the Czar’s sacred name was being taken in vain; and in proof he appended to the complaint a romance in which the justice of the peace is made to appear about once every ten lines, and sometimes in a drunken condition.

Therefore, in order to avoid all unpleasantness, it will be better to describe the department in question only as a certain department. So, in a certain department there was a certain official—not a very high one, it must be allowed—short of stature, somewhat pock-marked, red-haired, and short-sighted, with a bald forehead, wrinkled cheeks, and a complexion of the kind known as sanguine. The St. Petersburg climate was responsible for this. As for his official status, he was what is called a perpetual titular councillor, over which, as is well known, some writers make merry, and crack their jokes, obeying the praiseworthy custom of attacking those who cannot bite back.

His family name was Bashmachkin. This name is evidently derived from “bashmak” (shoe); but when, at what time, and in what manner, is not known. His father and grandfather, and all the Bashmachkins, always wore boots, which only had new heels two or three times a year. His name was Akakiy Akakievitch. It may strike the reader as rather singular and far-fetched, but he may rest assured that it was by no means far-fetched, and that the circumstances were such that it would have been impossible to give him any other.

This is how it came about. Akakiy Akakievitch was born, if my memory fails me not, in the evening of the 23rd of March. His mother, the wife of a Government official and a very fine woman, made all due arrangements for having the child baptised. She was lying on the bed opposite the door; on her right stood the godfather, Ivan Ivanovitch Eroshkin, a most estimable man, who served as presiding officer of the senate; and the godmother, Anna Semenovna Byelobrushkova, the wife of an officer of the quarter, and a woman of rare virtues. They offered the mother her choice of three names, Mokiya, Sossiya, or that the child should be called after the martyr Khozdazat.

“No,” said the good woman, “all those names are poor.” In order to please her they opened the calendar to another place; three more names appeared, Triphiliy, Dula, and Varakhasiy.

“This is a judgment,” said the old woman.

“What names! I truly never heard the like. Varada or Varukh might have been borne, but not Triphiliy and Varakhasiy!”

They turned to another page and found Pavsikakhiy and Vakhtisiy.

“Now I see,” said the old woman, “that it is plainly fate. And since such is the case, it will be better to name him after his father. His father’s name was Akakiy, so let his son’s be Akakiy too.”

In this manner he became Akakiy Akakievitch. They christened the child, whereat he wept and made a grimace, as though he foresaw that he was to be a titular councillor. In this manner did it all come about. We have mentioned it in order that the reader might see for himself that it was a case of necessity, and that it was utterly impossible to give him any other name. When and how he entered the department, and who appointed him, no one could remember. However much the directors and chiefs of all kinds were changed, he was always to be seen in the same place, the same attitude, the same occupation; so that it was afterwards affirmed that he had been born in undress uniform with a bald head.

No respect was shown him in the department. The porter not only did not rise from his seat when he passed, but never even glanced at him, any more than if a fly had flown through the reception-room. His superiors treated him in coolly despotic fashion. Some sub-chief would thrust a paper under his nose without so much as saying, “Copy,” or “Here’s a nice interesting affair,” or anything else agreeable, as is customary amongst well-bred officials. And he took it, looking only at the paper and not observing who handed it to him, or whether he had the right to do so; simply took it, and set about copying it.

The young officials laughed at and made fun of him, so far as their official wit permitted; told in his presence various stories concocted about him, and about his landlady, an old woman of seventy; declared that she beat him; asked when the wedding was to be; and strewed bits of paper over his head, calling them snow. But Akakiy Akakievitch answered not a word, any more than if there had been no one there besides himself. It even had no effect upon his work: amid all these annoyances he never made a single mistake in a letter. But if the joking became wholly unbearable, as when they jogged his hand and prevented his attending to his work, he would exclaim, “Leave me alone! Why do you insult me?”

And there was something strange in the words and the voice in which they were uttered. There was in it something which moved to pity; so much that one young man, a new-comer, who, taking pattern by the others, had permitted himself to make sport of Akakiy, suddenly stopped short, as though all about him had undergone a transformation, and presented itself in a different aspect. Some unseen force repelled him from the comrades whose acquaintance he had made, on the supposition that they were well-bred and polite men. Long afterwards, in his gayest moments, there recurred to his mind the little official with the bald forehead, with his heart-rending words, “Leave me alone! Why do you insult me?”

In these moving words, other words resounded—”I am thy brother.” And the young man covered his face with his hand; and many a time afterwards, in the course of his life, shuddered at seeing how much inhumanity there is in man, how much savage coarseness is concealed beneath delicate, refined worldliness, and even, O God! in that man whom the world acknowledges as honourable and noble. It would be difficult to find another man who lived so entirely for his duties. It is not enough to say that Akakiy laboured with zeal: no, he laboured with love. In his copying, he found a varied and agreeable employment.

Enjoyment was written on his face: some letters were even favourites with him; and when he encountered these, he smiled, winked, and worked with his lips, till it seemed as though each letter might be read in his face, as his pen traced it. If his pay had been in proportion to his zeal, he would, perhaps, to his great surprise, have been made even a councillor of state. But he worked, as his companions, the wits, put it, like a horse in a mill.

Moreover, it is impossible to say that no attention was paid to him. One director being a kindly man, and desirous of rewarding him for his long service, ordered him to be given something more important than mere copying. So he was ordered to make a report of an already concluded affair to another department: the duty consisting simply in changing the heading and altering a few words from the first to the third person. This caused him so much toil that he broke into a perspiration, rubbed his forehead, and finally said, “No, give me rather something to copy.” After that they let him copy on forever.

Outside this copying, it appeared that nothing existed for him. He gave no thought to his clothes: his undress uniform was not green, but a sort of rusty- meal colour. The collar was low, so that his neck, in spite of the fact that it was not long, seemed inordinately so as it emerged from it, like the necks of those plaster cats which wag their heads, and are carried about upon the heads of scores of image sellers. And something was always sticking to his uniform, either a bit of hay or some trifle. Moreover, he had a peculiar knack, as he walked along the street, of arriving beneath a window just as all sorts of rubbish were being flung out of it: hence he always bore about on his hat scraps of melon rinds and other such articles.

Never once in his life did he give heed to what was going on every day in the street; while it is well known that his young brother officials train the range of their glances till they can see when any one’s trouser straps come undone upon the opposite sidewalk, which always brings a malicious smile to their faces. But Akakiy Akakievitch saw in all things the clean, even strokes of his written lines; and only when a horse thrust his nose, from some unknown quarter, over his shoulder, and sent a whole gust of wind down his neck from his nostrils, did he observe that he was not in the middle of a page, but in the middle of the street.

On reaching home, he sat down at once at the table, supped his cabbage soup up quickly, and swallowed a bit of beef with onions, never noticing their taste, and gulping down everything with flies and anything else which the Lord happened to send at the moment.

His stomach filled, he rose from the table, and copied papers which he had brought home. If there happened to be none, he took copies for himself, for his own gratification, especially if the document was

noteworthy, not on account of its style, but of its being addressed to some distinguished person. Even at the hour when the grey St. Petersburg sky had quite dispersed, and all the official world had eaten or dined, each as he could, in accordance with the salary he received and his own fancy; when all were resting from the departmental jar of pens, running to and fro from their own and other people’s indispensable occupations, and from all the work that an uneasy man makes willingly for himself, rather than what is necessary; when officials hasten to dedicate to pleasure the time which is left to them, one bolder than the rest going to the theatre; another, into the street looking under all the bonnets; another wasting his evening in compliments to some pretty girl, the star of a small official circle; another—and this is the common case of all— visiting his comrades on the fourth or third floor, in two small rooms with an ante-room or kitchen, and some pretensions to fashion, such as a lamp or some other trifle which has cost many a sacrifice of dinner or pleasure trip; in a word, at the hour when all officials disperse among the contracted quarters of their friends, to play whist, as they sip their tea from glasses with a kopek’s worth of sugar, smoke long pipes, relate at times some bits of gossip which a Russian man can never, under any circumstances, refrain from, and, when there is nothing else to talk of, repeat eternal anecdotes about the commandant to whom they had sent word that the tails of the horses on the Falconet Monument had been cut off, when all strive to divert themselves, Akakiy Akakievitch indulged in no kind of diversion. No one could ever say that he had seen him at any kind of evening party. Having written to his heart’s content, he lay down to sleep, smiling at the thought of the coming day—of what God might send him to copy on the morrow.

Thus flowed on the peaceful life of the man, who, with a salary of four hundred rubles, understood how to be content with his lot; and thus it would have continued to flow on, perhaps, to extreme old age, were it not that there are various ills strewn along the path of life for titular councillors as well as for private, actual, court, and every other species of councillor, even for those who never give any advice or take any themselves.

There exists in St. Petersburg a powerful foe of all who receive a salary of four hundred rubles a year, or thereabouts. This foe is no other than the Northern cold, although it is said to be very healthy. At nine o’clock in the morning, at the very hour when the streets are filled with men bound for the various official departments, it begins to bestow such powerful and piercing nips on all noses impartially that the poor officials really do not know what to do with them. At an hour when the foreheads of even those who occupy exalted positions ache with the cold, and tears start to their eyes, the poor titular councillors are sometimes quite unprotected. Their only salvation lies in traversing as quickly as possible, in their thin little cloaks, five or six streets, and then warming their feet in the porter’s room, and so thawing all their talents and qualifications for official service, which had become frozen on the way.

Akakiy Akakievitch had felt for some time that his back and shoulders suffered with peculiar poignancy, in spite of the fact that he tried to traverse the distance with all possible speed. He began finally to wonder whether the fault did not lie in his cloak. He examined it thoroughly at home, and discovered that in two places, namely, on the back and shoulders, it had become thin as gauze: the cloth was worn to such a degree that he could see through it, and the lining had fallen into pieces. You must know that Akakiy Akakievitch’s cloak served as an object of ridicule to the officials: they even refused it the noble name of cloak, and called it a cape. In fact, it was of singular make: its collar diminishing year by year, but serving to patch its other parts.

The patching did not exhibit great skill on the part of the tailor, and was, in fact, baggy and ugly. Seeing how the matter stood, Akakiy Akakievitch decided that it would be necessary to take the cloak to Petrovitch, the tailor, who lived somewhere on the fourth floor up a dark staircase, and who, in spite of his having but one eye, and pock-marks all over his face, busied himself with considerable success in repairing the trousers and coats of officials and others; that is to say, when he was sober and not nursing some other scheme in his head.

It is not necessary to say much about this tailor; but, as it is the custom to have the character of each personage in a novel clearly defined, there is no help for it, so here is Petrovitch the tailor. At first he was called only Grigoriy, and was some gentleman’s serf; he commenced calling himself Petrovitch from the time when he received his free papers, and further began to drink heavily on all holidays, at first on the great ones, and then on all church festivities without discrimination, wherever a cross stood in the calendar. On this point he was faithful to ancestral custom; and when quarrelling with his wife, he called her a low female and a German.

As we have mentioned his wife, it will be necessary to say a word or two about her. Unfortunately, little is known of her beyond the fact that Petrovitch has a wife, who wears a cap and a dress; but cannot lay claim to beauty, at least, no one but the soldiers of the guard even looked under her cap when they met her.

Ascending the staircase which led to Petrovitch’s room—which staircase was all soaked with dish-water, and reeked with the smell of spirits which affects the eyes, and is an inevitable adjunct to all dark stairways in St. Petersburg houses—ascending the stairs, Akakiy Akakievitch pondered how much Petrovitch would ask, and mentally resolved not to give more than two rubles. The door was open; for the mistress, in cooking some fish, had raised such a smoke in the kitchen that not even the beetles were visible.

Akakiy Akakievitch passed through the kitchen unperceived, even by the housewife, and at length reached a room where he beheld Petrovitch seated on a large unpainted table, with his legs tucked under him like a Turkish pasha. His feet were bare, after the fashion of tailors who sit at work; and the first thing which caught the eye was his thumb, with a deformed nail thick and strong as a turtle’s shell. About Petrovitch’s neck hung a skein of silk and thread, and upon his knees lay some old garment. He had been trying unsuccessfully for three minutes to thread his needle, and was enraged at the darkness and even at the thread, growling in a low voice, “It won’t go through, the barbarian! you pricked me, you rascal!”

Akakiy Akakievitch was vexed at arriving at the precise moment when Petrovitch was angry; he liked to order something of Petrovitch when the latter was a little downhearted, or, as his wife expressed it, “when he had settled himself with brandy, the one-eyed devil!” Under such circumstances, Petrovitch generally came down in his price very readily, and even bowed and returned thanks. Afterwards, to be sure, his wife would come, complaining that her husband was drunk, and so had fixed the price too low; but, if only a ten-kopek piece were added, then the matter was settled. But now it appeared that Petrovitch was in a sober condition, and therefore rough, taciturn, and inclined to demand Satan only knows what price.

Akakiy Akakievitch felt this, and would gladly have beat a retreat; but he was in for it. Petrovitch screwed up his one eye very intently at him, and Akakiy Akakievitch involuntarily said: “How do you do, Petrovitch?”

“I wish you a good morning, sir,” said Petrovitch, squinting at Akakiy Akakievitch’s hands, to see what sort of booty he had brought.

“Ah! I—to you, Petrovitch, this—” It must be known that Akakiy Akakievitch expressed himself chiefly by prepositions, adverbs, and scraps of phrases which had no meaning whatever.

If the matter was a very difficult one, he had a habit of never completing his sentences; so that frequently, having begun a phrase with the words, “This, in fact, is quite—” he forgot to go on, thinking that he had already finished it.

“What is it?” asked Petrovitch, and with his one eye scanned Akakievitch’s whole uniform from the collar down to the cuffs, the back, the tails and the button-holes, all of which were well known to him, since they were his own handiwork. Such is the habit of tailors; it is the first thing they do on meeting one.

“But I, here, this—Petrovitch—a cloak, cloth—here you see, everywhere, in different places, it is quite strong—it is a little dusty, and looks old, but it is new, only here in one place it is a little—on the back, and here on one of the shoulders, it is a little worn, yes, here on this shoulder it is a little—do you see? that is all. And a little work—”

Petrovitch took the cloak, spread it out, to begin with, on the table, looked hard at it, shook his head, reached out his hand to the window-sill for his snuff-box, adorned with the portrait of some general, though what general is unknown, for the place where the face should have been had been rubbed through by the finger, and a square bit of paper had been pasted over it. Having taken a pinch of snuff, Petrovitch held up the cloak, and inspected it against the light, and again shook his head once more. After which he again lifted the general-adorned lid with its bit of pasted paper, and having stuffed his nose with snuff, closed and put away the snuff-box, and said finally, “No, it is impossible to mend it; it’s a wretched garment!”

Akakiy Akakievitch’s heart sank at these words.

“Why is it impossible, Petrovitch?” he said, almost in the pleading voice of a child; “all that ails it is, that it is worn on the shoulders. You must have some pieces—”

“Yes, patches could be found, patches are easily found,” said Petrovitch, “but there’s nothing to sew them to. The thing is completely rotten; if you put a needle to it—see, it will give way.”

“Let it give way, and you can put on another patch at once.”

“But there is nothing to put the patches on to; there’s no use in strengthening it; it is too far gone. It’s lucky that it’s cloth; for, if the wind were to blow, it would fly away.”

“Well, strengthen it again. How will this, in fact—”

“No,” said Petrovitch decisively, “there is nothing to be done with it. It’s a thoroughly bad job. You’d better, when the cold winter weather comes on, make yourself some gaiters out of it, because stockings are not warm. The Germans invented them in order to make more money.”

Petrovitch loved, on all occasions, to have a fling at the Germans. “But it is plain you must have a new cloak.”

At the word “new,” all grew dark before Akakiy Akakievitch’s eyes, and everything in the room began to whirl round. The only thing he saw clearly was the general with the paper face on the lid of Petrovitch’s snuff-box. “A new one?” said he, as if still in a dream: “why, I have no money for that.”

“Yes, a new one,” said Petrovitch, with barbarous composure.

“Well, if it came to a new one, how would it—?”

“You mean how much would it cost?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you would have to lay out a hundred and fifty or more,” said Petrovitch, and pursed up his lips significantly. He liked to produce powerful effects, liked to stun utterly and suddenly, and then to glance sideways to see what face the stunned person would put on the matter.

“A hundred and fifty rubles for a cloak!” shrieked poor Akakiy Akakievitch, perhaps for the first time in his life, for his voice had always been distinguished for softness.

“Yes, sir,” said Petrovitch, “for any kind of cloak. If you have a marten fur on the collar, or a silk-lined hood, it will mount up to two hundred.”

“Petrovitch, please,” said Akakiy Akakievitch in a beseeching tone, not hearing, and not trying to hear, Petrovitch’s words, and disregarding all his “effects,” “some repairs, in order that it may wear yet a little longer.”

“No, it would only be a waste of time and money,” said Petrovitch; and Akakiy Akakievitch went away after these words, utterly discouraged. But Petrovitch stood for some time after his departure, with significantly compressed lips, and without betaking himself to his work, satisfied that he would not be dropped, and an artistic tailor employed.

Akakiy Akakievitch went out into the street as if in a dream. “Such an affair!” he said to himself: “I did not think it had come to—” and then after a pause, he added, “Well, so it is! see what it has come to at last! and I never imagined that it was so!” Then followed a long silence, after which he exclaimed, “Well, so it is! see what already—nothing unexpected that—it would be nothing—what a strange circumstance!” So saying, instead of going home, he went in exactly the opposite direction without himself suspecting it.

On the way, a chimney-sweep bumped up against him, and blackened his shoulder, and a whole hatful of rubbish landed on him from the top of a house which was building. He did not notice it; and only when he ran against a watchman, who, having planted his halberd beside him, was shaking some snuff from his box into his horny hand, did he recover himself a little, and that because the watchman said, “Why are you poking yourself into a man’s very face? Haven’t you the pavement?”

This caused him to look about him, and turn towards home. There only, he finally began to collect his thoughts, and to survey his position in its clear and actual light, and to argue with himself, sensibly and frankly, as with a reasonable friend with whom one can discuss private and personal matters.

“No,” said Akakiy Akakievitch, “it is impossible to reason with Petrovitch now; he is that—evidently his wife has been beating him. I’d better go to him on Sunday morning; after Saturday night he will be a little cross-eyed and sleepy, for he will want to get drunk, and his wife won’t give him any money; and at such a time, a ten-kopek piece in his hand will—he will become more fit to reason with, and then the cloak, and that—”

Thus argued Akakiy Akakievitch with himself, regained his courage, and waited until the first Sunday, when, seeing from afar that Petrovitch’s wife had left the house, he went straight to him.

Petrovitch’s eye was, indeed, very much askew after Saturday: his head drooped, and he was very sleepy; but for all that, as soon as he knew what it was a question of, it seemed as though Satan jogged his memory. “Impossible,” said he: “please to order a new one.”

Thereupon Akakiy Akakievitch handed over the ten- kopek piece. “Thank you, sir; I will drink your good health,” said Petrovitch: “but as for the cloak, don’t trouble yourself about it; it is good for nothing. I will

make you a capital new one, so let us settle about it now.”

Akakiy Akakievitch was still for mending it; but Petrovitch would not hear of it, and said, “I shall certainly have to make you a new one, and you may depend upon it that I shall do my best. It may even be, as the fashion goes, that the collar can be fastened by silver hooks under a flap.”

Then Akakiy Akakievitch saw that it was impossible to get along without a new cloak, and his spirit sank utterly. How, in fact, was it to be done? Where was the money to come from? He might, to be sure, depend, in part, upon his present at Christmas; but that money had long been allotted beforehand. He must have some new trousers, and pay a debt of long standing to the shoemaker for putting new tops to his old boots, and he must order three shirts from the seamstress, and a couple of pieces of linen.

In short, all his money must be spent; and even if the director should be so kind as to order him to receive forty-five rubles instead of forty, or even fifty, it would be a mere nothing, a mere drop in the ocean towards the funds necessary for a cloak: although he knew that Petrovitch was often wrong-headed enough to blurt out some outrageous price, so that even his own wife could not refrain from exclaiming, “Have you lost your senses, you fool?” At one time he would not work at any price, and now it was quite likely

that he had named a higher sum than the cloak would cost.

But although he knew that Petrovitch would undertake to make a cloak for eighty rubles, still, where was he to get the eighty rubles from? He might possibly manage half, yes, half might be procured, but where was the other half to come from? But the reader must first be told where the first half came from. Akakiy Akakievitch had a habit of putting, for every ruble he spent, a groschen into a small box, fastened with a lock and key, and with a slit in the top for the reception of money.

At the end of every half-year he counted over the heap of coppers, and changed it for silver. This he had done for a long time, and in the course of years, the sum had mounted up to over forty rubles. Thus he had one half on hand; but where was he to find the other half? where was he to get another forty rubles from? Akakiy Akakievitch thought and thought, and decided that it would be necessary to curtail his ordinary expenses, for the space of one year at least, to dispense with tea in the evening; to burn no candles, and, if there was anything which he must do, to go into his landlady’s room, and work by her light. When he went into the street, he must walk as lightly as he could, and as cautiously, upon the stones, almost upon tiptoe, in order not to wear his heels down in too short a time; he must give the laundress as little to wash as possible; and, in order not to wear out his clothes, he must take them off, as soon as he got home, and wear only his cotton dressing-gown, which had been long and carefully saved.

To tell the truth, it was a little hard for him at first to accustom himself to these deprivations; but he got used to them at length, after a fashion, and all went smoothly. He even got used to being hungry in the evening, but he made up for it by treating himself, so to say, in spirit, by bearing ever in mind the idea of his future cloak. From that time forth his existence seemed to become, in some way, fuller, as if he were married, or as if some other man lived in him, as if, in fact, he were not alone, and some pleasant friend had consented to travel along life’s path with him, the friend being no other than the cloak, with thick wadding and a strong lining incapable of wearing out.

He became more lively, and even his character grew firmer, like that of a man who has made up his mind, and set himself a goal. From his face and gait, doubt and indecision, all hesitating and wavering traits disappeared of themselves. Fire gleamed in his eyes, and occasionally the boldest and most daring ideas flitted through his mind; why not, for instance, have marten fur on the collar? The thought of this almost made him absent-minded. Once, in copying a letter, he nearly made a mistake, so that he exclaimed almost aloud, “Ugh!” and crossed himself. Once, in the course of every month, he had a conference with Petrovitch on the subject of the cloak, where it would be better to buy the cloth, and the colour, and the price. He always returned home satisfied, though troubled, reflecting that the time would come at last

when it could all be bought, and then the cloak made.

The affair progressed more briskly than he had expected. Far beyond all his hopes, the director awarded neither forty nor forty-five rubles for Akakiy Akakievitch’s share, but sixty. Whether he suspected that Akakiy Akakievitch needed a cloak, or whether it was merely chance, at all events, twenty extra rubles were by this means provided. This circumstance hastened matters. Two or three months more of hunger and Akakiy Akakievitch had accumulated about eighty rubles.

His heart, generally so quiet, began to throb. On the first possible day, he went shopping in company with Petrovitch. They bought some very good cloth, and at a reasonable rate too, for they had been considering the matter for six months, and rarely let a month pass without their visiting the shops to inquire prices. Petrovitch himself said that no better cloth could be had. For lining, they selected a cotton stuff, but so firm and thick that Petrovitch declared it to be better than silk, and even prettier and more glossy. They did not buy the marten fur, because it was, in fact, dear, but in its stead, they picked out the very best of cat-skin which could be found in the shop, and which might, indeed, be taken for marten at a distance.

Petrovitch worked at the cloak two whole weeks, for there was a great deal of quilting: otherwise it would have been finished sooner. He charged twelve rubles for the job, it could not possibly have been done for less. It was all sewed with silk, in small, double seams; and Petrovitch went over each seam afterwards with his own teeth, stamping in various patterns.

It was—it is difficult to say precisely on what day, but probably the most glorious one in Akakiy Akakievitch’s life, when Petrovitch at length brought home the cloak. He brought it in the morning, before the hour when it was necessary to start for the department. Never did a cloak arrive so exactly in the nick of time; for the severe cold had set in, and it seemed to threaten to increase. Petrovitch brought the cloak himself as befits a good tailor.

On his countenance was a significant expression, such as Akakiy Akakievitch had never beheld there. He seemed fully sensible that he had done no small deed, and crossed a gulf separating tailors who only put in linings, and execute repairs, from those who make new things. He took the cloak out of the pocket handkerchief in which he had brought it. The handkerchief was fresh from the laundress, and he put it in his pocket for use. Taking out the cloak, he gazed proudly at it, held it up with both hands, and flung it skilfully over the shoulders of Akakiy Akakievitch. Then he pulled it and fitted it down behind with his hand, and he draped it around Akakiy Akakievitch without buttoning it. Akakiy Akakievitch, like an experienced man, wished to try the sleeves.

Petrovitch helped him on with them, and it turned out that the sleeves were satisfactory also. In short, the cloak appeared to be perfect, and most seasonable. Petrovitch did not neglect to observe that it

was only because he lived in a narrow street, and had no signboard, and had known Akakiy Akakievitch so long, that he had made it so cheaply; but that if he had been in business on the Nevsky Prospect, he would have charged seventy-five rubles for the making alone. Akakiy Akakievitch did not care to argue this point with Petrovitch.

He paid him, thanked him, and set out at once in his new cloak for the department. Petrovitch followed him, and, pausing in the street, gazed long at the cloak in the distance, after which he went to one side expressly to run through a crooked alley, and emerge again into the street beyond to gaze once more upon the cloak from another point, namely, directly in front.

Meantime Akakiy Akakievitch went on in holiday mood. He was conscious every second of the time that he had a new cloak on his shoulders; and several times he laughed with internal satisfaction. In fact, there were two advantages, one was its warmth, the other its beauty. He saw nothing of the road, but suddenly found himself at the department. He took off his cloak in the ante-room, looked it over carefully, and confided it to the especial care of the attendant. It is impossible to say precisely how it was that everyone in the department knew at once that Akakiy Akakievitch had a new cloak, and that the “cape” no longer existed.

All rushed at the same moment into the ante-room to inspect it. They congratulated him and said pleasant things to him, so that he began at first to smile and then to grow ashamed. When all surrounded him, and said that the new cloak must be “christened,” and that he must give a whole evening at least to this, Akakiy Akakievitch lost his head completely, and did not know where he stood, what to answer, or how to get out of it. He stood blushing all over for several minutes, and was on the point of assuring them with great simplicity that it was not a new cloak, that it was so and so, that it was in fact the old “cape.”

At length one of the officials, a sub-chief probably, in order to show that he was not at all proud, and on good terms with his inferiors, said, “So be it, only I will give the party instead of Akakiy Akakievitch; I invite you all to tea with me to-night; it happens quite a propos, as it is my name-day.” The officials naturally at once offered the sub-chief their congratulations and accepted the invitations with pleasure. Akakiy Akakievitch would have declined, but all declared that it was discourteous, that it was simply a sin and a shame, and that he could not possibly refuse. Besides, the notion became pleasant to him when he recollected that he should thereby have a chance of wearing his new cloak in the evening also.

That whole day was truly a most triumphant festival day for Akakiy Akakievitch. He returned home in the most happy frame of mind, took off his cloak, and hung it carefully on the wall, admiring afresh the cloth and the lining. Then he brought out his old, worn-out cloak, for comparison. He looked at it and laughed, so vast was the difference. And long after dinner he laughed again when the condition of the “cape” recurred to his mind. He dined cheerfully, and after dinner wrote nothing, but took his ease for a while on the bed, until it got dark. Then he dressed himself leisurely, put on his cloak, and stepped out into the street.

Where the host lived, unfortunately we cannot say: our memory begins to fail us badly; and the houses and streets in St. Petersburg have become so mixed up in our head that it is very difficult to get anything out of it again in proper form. This much is certain, that the official lived in the best part of the city; and therefore it must have been anything but near to Akakiy Akakievitch’s residence. Akakiy Akakievitch was first obliged to traverse a kind of wilderness of deserted, dimly-lighted streets; but in proportion as he approached the official’s quarter of the city, the streets became more lively, more populous, and more brilliantly illuminated.

Pedestrians began to appear; handsomely dressed ladies were more frequently encountered; the men had otter skin collars to their coats; peasant waggoners, with their grate-like sledges stuck over with brass-headed nails, became rarer; whilst on the other hand, more and more drivers in red velvet caps, lacquered sledges and bear-skin coats began to appear, and carriages with rich hammer-cloths flew swiftly through the streets, their wheels scrunching the snow. Akakiy Akakievitch gazed upon all this as upon a novel sight.

He had not been in the streets during the evening for years. He halted out of curiosity before a shop-window to look at a picture representing a handsome woman, who had thrown off her shoe, thereby baring her whole foot in a very pretty way; whilst behind her the head of a man with whiskers and a handsome moustache peeped through the doorway of another room. Akakiy Akakievitch shook his head and laughed, and then went on his way.

Why did he laugh? Either because he had met with a thing utterly unknown, but for which every one cherishes nevertheless, some sort of feeling; or else he thought, like many officials, as follows: “Well, those French! What is to be said? If they do go in anything of that sort, why—” But possibly he did not think at all.

Akakiy Akakievitch at length reached the house in which the sub-chief lodged. The subchief lived in fine style: the staircase was lit by a lamp; his apartment being on the second floor. On entering the vestibule, Akakiy Akakievitch beheld a whole row of goloshes on the floor. Among them, in the centre of the room, stood a samovar humming and emitting clouds of steam. On the walls hung all sorts of coats and cloaks, among which there were even some with beaver collars or velvet facings. Beyond, the buzz of conversation was audible, and became clear and loud when the servant came out with a trayful of empty glasses, cream-jugs, and sugar-bowls. It was evident that the officials had arrived long before and had already finished their first glass of tea.

Akakiy Akakievitch, having hung up his own cloak, entered the inner room. Before him all at once appeared lights, officials, pipes, and card-tables; and he was bewildered by the sound of rapid conversation rising from all the tables, and the noise of moving chairs. He halted very awkwardly in the middle of the room, wondering what he ought to do. But they had seen him.

They received him with a shout, and all thronged at once into the ante-room, and there took another look at his cloak. Akakiy Akakievitch, although somewhat confused, was frank-hearted, and could not refrain from rejoicing when he saw how they praised his cloak. Then, of course, they all dropped him and his cloak, and returned, as was proper, to the tables set out for whist.

All this, the noise, the talk, and the throng of people was rather overwhelming to Akakiy Akakievitch. He simply did not know where he stood, or where to put his hands, his feet, and his whole body. Finally he sat down by the players, looked at the cards, gazed at the face of one and another, and after a while began to gape, and to feel that it was wearisome, the more so as the hour was already long past when he usually went to bed. He wanted to take leave of the host; but they would not let him go, saying that he must not fail to drink a glass of champagne in honour of his new garment. In the course of an hour, supper, consisting of vegetable salad, cold veal, pastry, confectioner’s pies, and champagne, was served. They made Akakiy Akakievitch drink two glasses of champagne, after which he felt things grow livelier.

Still, he could not forget that it was twelve o’clock, and that he should have been at home long ago. In order that the host might not think of some excuse for detaining him, he stole out of the room quickly, sought out, in the ante-room, his cloak, which, to his sorrow, he found lying on the floor, brushed it, picked off every speck upon it, put it on his shoulders, and descended the stairs to the street.

In the street all was still bright. Some petty shops, those permanent clubs of servants and all sorts of folk, were open. Others were shut, but, nevertheless, showed a streak of light the whole length of the door-crack, indicating that they were not yet free of company, and that probably some domestics, male and female, were finishing their stories and conversations whilst leaving their masters in complete ignorance as to their whereabouts. Akakiy Akakievitch went on in a happy frame of mind: he even started to run, without knowing why, after some lady, who flew past like a flash of lightning.

But he stopped short, and went on very quietly as before, wondering why he had quickened his pace. Soon there spread before him those deserted streets, which are not cheerful in the daytime, to say nothing of the evening. Now they were even more dim and lonely: the lanterns began to grow rarer, oil, evidently, had been less liberally supplied. Then came wooden houses and fences: not a soul anywhere; only the snow sparkled in the streets, and mournfully veiled the low-roofed cabins with their closed shutters. He approached the spot where the street crossed a vast square with houses barely visible on its farther side, a

square which seemed a fearful desert.

Afar, a tiny spark glimmered from some watchman’s box, which seemed to stand on the edge of the world. Akakiy Akakievitch’s cheerfulness diminished at this point in a marked degree. He entered the square, not without an involuntary sensation of fear, as though his heart warned him of some evil. He glanced back and on both sides, it was like a sea about him.

“No, it is better not to look,” he thought, and went on, closing his eyes. When he opened them, to see whether he was near the end of the square, he suddenly beheld, standing just before his very nose, some bearded individuals of precisely what sort he could not make out. All grew dark before his eyes, and his heart throbbed.

“But, of course, the cloak is mine!” said one of them in a loud voice, seizing hold of his collar. Akakiy Akakievitch was about to shout “watch,” when the second man thrust a fist, about the size of a man’s head, into his mouth, muttering, “Now scream!”

Akakiy Akakievitch felt them strip off his cloak and give him a push with a knee: he fell headlong upon the snow, and felt no more. In a few minutes he recovered consciousness and rose to his feet; but no one was there. He felt that it was cold in the square, and that his cloak was gone; he began to shout, but his voice did not appear to reach to the outskirts of the square. In despair, but without ceasing to shout, he started at a run across the square, straight towards the watchbox, beside which stood the watchman, leaning on his halberd, and apparently curious to know what kind of a customer was running towards him and shouting.

Akakiy Akakievitch ran up to him, and began in a sobbing voice to shout that he was asleep, and attended to nothing, and did not see when a man was robbed. The watchman replied that he had seen two men stop him in the middle of the square, but supposed that they were friends of his; and that, instead of scolding vainly, he had better go to the police on the morrow, so that they might make a search for whoever had stolen the cloak.

Akakiy Akakievitch ran home in complete disorder; his hair, which grew very thinly upon his temples and the back of his head, wholly disordered; his body, arms, and legs covered with snow. The old woman, who was mistress of his lodgings, on hearing a terrible knocking, sprang hastily from her bed, and, with only one shoe on, ran to open the door, pressing the sleeve of her chemise to her bosom out of modesty; but when she had opened it, she fell back on beholding Akakiy Akakievitch in such a state.

When he told her about the affair, she clasped her hands, and said that he must go straight to the district chief of police, for his subordinate would turn up his nose, promise well, and drop the matter there. The very best thing to do, therefore, would be to go to the district chief, whom she knew, because Finnish Anna, her former cook, was now nurse at his house. She often saw him passing the house; and he was at church every Sunday, praying, but at the same time gazing cheerfully at everybody; so that he must be a good man, judging from all appearances. Having listened to this opinion, Akakiy Akakievitch betook himself sadly

to his room; and how he spent the night there anyone who can put himself in another’s place may readily imagine.

Early in the morning, he presented himself at the district chief’s, but was told that this official was asleep. He went again at ten and was again informed that he was asleep; at eleven, and they said: “The superintendent is not at home;” at dinner time, and the clerks in the anteroom would not admit him on any terms, and insisted upon knowing his business. So that at last, for once in his life, Akakiy Akakievitch felt an inclination to show some spirit, and said curtly that he must see the chief in person; that they ought not to presume to refuse him entrance; that he came from the department of justice, and that when he complained of them, they would see.

The clerks dared make no reply to this, and one of them went to call the chief, who listened to the strange story of the theft of the coat. Instead of directing his attention to the principal points of the matter, he began to question Akakiy Akakievitch: Why was he going home so late?

Was he in the habit of doing so, or had he been to some disorderly house? So that Akakiy Akakievitch got thoroughly confused, and left him without knowing whether the affair of his cloak was in proper train or not.

All that day, for the first time in his life, he never went near the department. The next day he made his appearance, very pale, and in his old cape, which had become even more shabby. The news of the robbery of the cloak touched many; although there were some officials present who never lost an opportunity, even such a one as the present, of ridiculing Akakiy Akakievitch. They decided to make a collection for him on the spot, but the officials had already spent a great deal in subscribing for the director’s portrait, and for some book, at the suggestion of the head of that division, who was a friend of the author; and so the sum was trifling.

One of them, moved by pity, resolved to help Akakiy Akakievitch with some good advice at least, and told him that he ought not to go to the police, for although it might happen that a police-officer, wishing to win the approval of his superiors, might hunt up the cloak by some means, still his cloak would remain in the possession of the police if he did not offer legal proof that it belonged to him. The best thing for him, therefore, would be to apply to a certain prominent personage; since this prominent personage, by entering into relations with the proper persons, could greatly expedite the matter.

As there was nothing else to be done, Akakiy Akakievitch decided to go to the prominent personage. What was the exact official position of the prominent personage remains unknown to this day. The reader must know that the prominent personage had but recently become a prominent personage, having up to that time been only an insignificant person. Moreover, his present position was not considered prominent in comparison with others still more so. But there is always a circle of people to whom what is insignificant in the eyes of others, is important enough.

Moreover, he strove to increase his importance by sundry devices; for instance, he managed to have the inferior officials meet him on the staircase when he entered upon his service; no one was to presume to come directly to him, but the strictest etiquette must be observed; the collegiate recorder must make a report to the government secretary, the government secretary to the titular councillor, or whatever other man was proper, and all business must come before him in this manner.

In Holy Russia all is thus contaminated with the love of imitation; every man imitates and copies his superior. They even say that a certain titular councillor, when promoted to the head of some small separate room, immediately partitioned off a private room for himself, called it the audience chamber, and posted at the door a lackey with red collar and braid, who grasped the handle of the door and opened to all comers; though the audience chamber could hardly hold an ordinary writing-table.

The manners and customs of the prominent personage were grand and imposing, but rather

exaggerated. The main foundation of his system was strictness. “Strictness, strictness, and

always strictness!” he generally said; and at the last word he looked significantly into the face of

the person to whom he spoke. But there was no necessity for this, for the half-score of

subordinates who formed the entire force of the office were properly afraid; on catching sight of

him afar off they left their work and waited, drawn up in line, until he had passed through the

room. His ordinary converse with his inferiors smacked of sternness, and consisted chiefly of

three phrases: “How dare you?” “Do you know whom you are speaking to?” “Do you realise

who stands before you?”

Otherwise he was a very kind-hearted man, good to his comrades, and ready to oblige; but

the rank of general threw him completely off his balance. On receiving any one of that rank, he

became confused, lost his way, as it were, and never knew what to do. If he chanced to be

amongst his equals he was still a very nice kind of man, a very good fellow in many respects,

and not stupid; but the very moment that he found himself in the society of people but one rank

lower than himself he became silent; and his situation aroused sympathy, the more so as he felt

himself that he might have been making an incomparably better use of his time. In his eyes there

was sometimes visible a desire to join some interesting conversation or group; but he was kept

back by the thought, “Would it not be a very great condescension on his part? Would it not be

familiar? and would he not thereby lose his importance?” And in consequence of such reflections

he always remained in the same dumb state, uttering from time to time a few monosyllabic

sounds, and thereby earning the name of the most wearisome of men.

To this prominent personage Akakiy Akakievitch presented himself, and this at the most

unfavourable time for himself though opportune for the prominent personage. The prominent

personage was in his cabinet conversing gaily with an old acquaintance and companion of his

childhood whom he had not seen for several years and who had just arrived when it was

announced to him that a person named Bashmatchkin had come. He asked abruptly, “Who is

he?”—”Some official,” he was informed. “Ah, he can wait! this is no time for him to call,” said

the important man.

It must be remarked here that the important man lied outrageously: he had said all he had to

say to his friend long before; and the conversation had been interspersed for some time with very

long pauses, during which they merely slapped each other on the leg, and said, “You think so,

Ivan Abramovitch!” “Just so, Stepan Varlamitch!” Nevertheless, he ordered that the official

14

should be kept waiting, in order to show his friend, a man who had not been in the service for a

long time, but had lived at home in the country, how long officials had to wait in his ante-room.

At length, having talked himself completely out, and more than that, having had his fill of

pauses, and smoked a cigar in a very comfortable arm-chair with reclining back, he suddenly

seemed to recollect, and said to the secretary, who stood by the door with papers of reports, “So

it seems that there is a tchinovnik waiting to see me. Tell him that he may come in.” On

perceiving Akakiy Akakievitch’s modest mien and his worn undress uniform, he turned abruptly

to him and said, “What do you want?” in a curt hard voice, which he had practised in his room in

private, and before the looking-glass, for a whole week before being raised to his present rank.

Akakiy Akakievitch, who was already imbued with a due amount of fear, became somewhat

confused: and as well as his tongue would permit, explained, with a rather more frequent

addition than usual of the word “that,” that his cloak was quite new, and had been stolen in the

most inhuman manner; that he had applied to him in order that he might, in some way, by his

intermediation—that he might enter into correspondence with the chief of police, and find the

cloak.

For some inexplicable reason this conduct seemed familiar to the prominent personage.

“What, my dear sir!” he said abruptly, “are you not acquainted with etiquette? Where have you

come from? Don’t you know how such matters are managed? You should first have entered a

complaint about this at the court below: it would have gone to the head of the department, then to

the chief of the division, then it would have been handed over to the secretary, and the secretary

would have given it to me.”

“But, your excellency,” said Akakiy Akakievitch, trying to collect his small handful of wits,

and conscious at the same time that he was perspiring terribly, “I, your excellency, presumed to

trouble you because secretaries—are an untrustworthy race.”

“What, what, what!” said the important personage. “Where did you get such courage?

Where did you get such ideas? What impudence towards their chiefs and superiors has spread

among the young generation!” The prominent personage apparently had not observed that

Akakiy Akakievitch was already in the neighborhood of fifty. If he could be called a young man,

it must have been in comparison with someone who was seventy. “Do you know to whom you

speak? Do you realise who stands before you? Do you realise it? do you realise it? I ask you!”

Then he stamped his foot and raised his voice to such a pitch that it would have frightened even a

different man from Akakiy Akakievitch.

Akakiy Akakievitch’s senses failed him; he staggered, trembled in every limb, and, if the

porters had not run to support him, would have fallen to the floor. They carried him out

insensible. But the prominent personage, gratified that the effect should have surpassed his

expectations, and quite intoxicated with the thought that his word could even deprive a man of

his senses, glanced sideways at his friend in order to see how he looked upon this, and perceived,

not without satisfaction, that his friend was in a most uneasy frame of mind, and even beginning,

on his part, to feel a trifle frightened.

Akakiy Akakievitch could not remember how he descended the stairs and got into the street.

He felt neither his hands nor feet. Never in his life had he been so rated by any high official, let

alone a strange one. He went staggering on through the snow-storm, which was blowing in the

streets, with his mouth wide open; the wind, in St. Petersburg fashion, darted upon him from all

quarters, and down every cross-street. In a twinkling it had blown a quinsy into his throat, and he

15

reached home unable to utter a word. His throat was swollen, and he lay down on his bed. So

powerful is sometimes a good scolding!

The next day a violent fever showed itself. Thanks to the generous assistance of the St.

Petersburg climate, the malady progressed more rapidly than could have been expected: and

when the doctor arrived, he found, on feeling the sick man’s pulse, that there was nothing to be

done, except to prescribe a fomentation, so that the patient might not be left entirely without the

beneficent aid of medicine; but at the same time, he predicted his end in thirty-six hours. After

this he turned to the landlady, and said, “And as for you, don’t waste your time on him: order his

pine coffin now, for an oak one will be too expensive for him.” Did Akakiy Akakievitch hear

these fatal words? and if he heard them, did they produce any overwhelming effect upon him?

Did he lament the bitterness of his life?—We know not, for he continued in a delirious condition.

Visions incessantly appeared to him, each stranger than the other. Now he saw Petrovitch, and

ordered him to make a cloak, with some traps for robbers, who seemed to him to be always under

the bed; and cried every moment to the landlady to pull one of them from under his coverlet.

Then he inquired why his old mantle hung before him when he had a new cloak. Next he fancied

that he was standing before the prominent person, listening to a thorough setting-down, and

saying, “Forgive me, your excellency!” but at last he began to curse, uttering the most horrible

words, so that his aged landlady crossed herself, never in her life having heard anything of the

kind from him, the more so as those words followed directly after the words “your excellency.”

Later on he talked utter nonsense, of which nothing could be made: all that was evident being,

that his incoherent words and thoughts hovered ever about one thing, his cloak.

At length poor Akakiy Akakievitch breathed his last. They sealed up neither his room nor

his effects, because, in the first place, there were no heirs, and, in the second, there was very little

to inherit beyond a bundle of goose-quills, a quire of white official paper, three pairs of socks,

two or three buttons which had burst off his trousers, and the mantle already known to the reader.

To whom all this fell, God knows. I confess that the person who told me this tale took no interest

in the matter. They carried Akakiy Akakievitch out and buried him.

And St. Petersburg was left without Akakiy Akakievitch, as though he had never lived there.

A being disappeared who was protected by none, dear to none, interesting to none, and who

never even attracted to himself the attention of those students of human nature who omit no

opportunity of thrusting a pin through a common fly, and examining it under the microscope. A

being who bore meekly the jibes of the department, and went to his grave without having done

one unusual deed, but to whom, nevertheless, at the close of his life appeared a bright visitant in

the form of a cloak, which momentarily cheered his poor life, and upon whom, thereafter, an

intolerable misfortune descended, just as it descends upon the mighty of this world!

Several days after his death, the porter was sent from the department to his lodgings, with an

order for him to present himself there immediately; the chief commanding it. But the porter had

to return unsuccessful, with the answer that he could not come; and to the question, “Why?”

replied, “Well, because he is dead! he was buried four days ago.” In this manner did they hear of

Akakiy Akakievitch’s death at the department, and the next day a new official sat in his place,

with a handwriting by no means so upright, but more inclined and slanting.

But who could have imagined that this was not really the end of Akakiy Akakievitch, that he

was destined to raise a commotion after death, as if in compensation for his utterly insignificant

life? But so it happened, and our poor story unexpectedly gains a fantastic ending.

16

A rumour suddenly spread through St. Petersburg that a dead man had taken to appearing on

the Kalinkin Bridge and its vicinity at night in the form of an official seeking a stolen cloak, and

that, under the pretext of its being the stolen cloak, he dragged, without regard to rank or calling,

every one’s cloak from his shoulders, be it cat-skin, beaver, fox, bear, sable; in a word, every sort

of fur and skin which men adopted for their covering. One of the department officials saw the

dead man with his own eyes and immediately recognised in him Akakiy Akakievitch. This,

however, inspired him with such terror that he ran off with all his might, and therefore did not

scan the dead man closely, but only saw how the latter threatened him from afar with his finger.

Constant complaints poured in from all quarters that the backs and shoulders, not only of titular

but even of court councillors, were exposed to the danger of a cold on account of the frequent

dragging off of their cloaks.

Arrangements were made by the police to catch the corpse, alive or dead, at any cost, and

punish him as an example to others in the most severe manner. In this they nearly succeeded; for

a watchman, on guard in Kirushkin Alley, caught the corpse by the collar on the very scene of

his evil deeds, when attempting to pull off the frieze coat of a retired musician. Having seized

him by the collar, he summoned, with a shout, two of his comrades, whom he enjoined to hold

him fast while he himself felt for a moment in his boot, in order to draw out his snuff-box and

refresh his frozen nose. But the snuff was of a sort which even a corpse could not endure. The

watchman having closed his right nostril with his finger, had no sooner succeeded in holding half

a handful up to the left than the corpse sneezed so violently that he completely filled the eyes of

all three. While they raised their hands to wipe them, the dead man vanished completely, so that

they positively did not know whether they had actually had him in their grip at all. Thereafter the

watchmen conceived such a terror of dead men that they were afraid even to seize the living, and

only screamed from a distance, “Hey, there! go your way!” So the dead tchinovnik began to

appear even beyond the Kalinkin Bridge, causing no little terror to all timid people.

But we have totally neglected that certain prominent personage who may really be

considered as the cause of the fantastic turn taken by this true history. First of all, justice compels

us to say that after the departure of poor, annihilated Akakiy Akakievitch he felt something like

remorse. Suffering was unpleasant to him, for his heart was accessible to many good impulses, in

spite of the fact that his rank often prevented his showing his true self. As soon as his friend had

left his cabinet, he began to think about poor Akakiy Akakievitch. And from that day forth, poor

Akakiy Akakievitch, who could not bear up under an official reprimand, recurred to his mind

almost every day. The thought troubled him to such an extent that a week later he even resolved

to send an official to him, to learn whether he really could assist him; and when it was reported

to him that Akakiy Akakievitch had died suddenly of fever, he was startled, hearkened to the

reproaches of his conscience, and was out of sorts for the whole day.

Wishing to divert his mind in some way, and drive away the disagreeable impression, he set

out that evening for one of his friends’ houses, where he found quite a large party assembled.

What was better, nearly everyone was of the same rank as himself, so that he need not feel in the

least constrained. This had a marvellous effect upon his mental state. He grew expansive, made

himself agreeable in conversation, in short, he passed a delightful evening. After supper he drank

a couple of glasses of champagne—not a bad recipe for cheerfulness, as everyone knows. The

champagne inclined him to various adventures; and he determined not to return home, but to go

and see a certain well-known lady of German extraction, Karolina Ivanovna, a lady, it appears,

with whom he was on a very friendly footing.

17

It must be mentioned that the prominent personage was no longer a young man, but a good

husband and respected father of a family. Two sons, one of whom was already in the service, and

a good-looking, sixteen-year-old daughter, with a rather retrousse but pretty little nose, came

every morning to kiss his hand and say, “Bonjour, papa.” His wife, a still fresh and good-looking

woman, first gave him her hand to kiss, and then, reversing the procedure, kissed his. But the

prominent personage, though perfectly satisfied in his domestic relations, considered it stylish to

have a friend in another quarter of the city. This friend was scarcely prettier or younger than his

wife; but there are such puzzles in the world, and it is not our place to judge them. So the

important personage descended the stairs, stepped into his sledge, said to the coachman, “To

Karolina Ivanovna’s,” and, wrapping himself luxuriously in his warm cloak, found himself in

that delightful frame of mind than which a Russian can conceive no better, namely, when you

think of nothing yourself, yet when the thoughts creep into your mind of their own accord, each

more agreeable than the other, giving you no trouble either to drive them away or seek them.

Fully satisfied, he recalled all the gay features of the evening just passed, and all the mots which

had made the little circle laugh. Many of them he repeated in a low voice, and found them quite

as funny as before; so it is not surprising that he should laugh heartily at them. Occasionally,

however, he was interrupted by gusts of wind, which, coming suddenly, God knows whence or

why, cut his face, drove masses of snow into it, filled out his cloak-collar like a sail, or suddenly

blew it over his head with supernatural force, and thus caused him constant trouble to disentangle

himself.

Suddenly the important personage felt some one clutch him firmly by the collar. Turning

round, he perceived a man of short stature, in an old, worn uniform, and recognised, not without

terror, Akakiy Akakievitch. The official’s face was white as snow, and looked just like a corpse’s.

But the horror of the important personage transcended all bounds when he saw the dead man’s

mouth open, and, with a terrible odour of the grave, gave vent to the following remarks: “Ah,

here you are at last! I have you, that—by the collar! I need your cloak; you took no trouble about

mine, but reprimanded me; so now give up your own.”

The pallid prominent personage almost died of fright. Brave as he was in the office and in

the presence of inferiors generally, and although, at the sight of his manly form and appearance,

every one said, “Ugh! how much character he has!” at this crisis, he, like many possessed of an

heroic exterior, experienced such terror, that, not without cause, he began to fear an attack of

illness. He flung his cloak hastily from his shoulders and shouted to his coachman in an

unnatural voice, “Home at full speed!” The coachman, hearing the tone which is generally

employed at critical moments and even accompanied by something much more tangible, drew

his head down between his shoulders in case of an emergency, flourished his whip, and flew on

like an arrow. In a little more than six minutes the prominent personage was at the entrance of

his own house. Pale, thoroughly scared, and cloakless, he went home instead of to Karolina

Ivanovna’s, reached his room somehow or other, and passed the night in the direst distress; so

that the next morning over their tea his daughter said, “You are very pale to-day, papa.” But papa

remained silent, and said not a word to any one of what had happened to him, where he had been,

or where he had intended to go.

This occurrence made a deep impression upon him. He even began to say: “How dare you? do you realise who stands before you?” less frequently to the under-officials, and if he did utter the words, it was only after having first learned the bearings of the matter. But the most noteworthy point was, that from that day forward the apparition of the dead tchinovnik ceased to be seen. Evidently the prominent personage’s cloak just fitted his shoulders; at all events, no more instances of his dragging cloaks from people’s shoulders were heard of. But many active and apprehensive persons could by no means reassure themselves, and asserted that the dead tchinovnik still showed himself in distant parts of the city.

In fact, one watchman in Kolomna saw with his own eyes the apparition come from behind a house. But being rather weak of body, he dared not arrest him, but followed him in the dark, until, at length, the apparition looked round, paused, and inquired, “What do you want?” at the same time showing a fist such as is never seen on living men. The watchman said, “It’s of no consequence,” and turned back instantly. But the apparition was much too tall, wore huge moustaches, and, directing its steps apparently towards the Obukhoff bridge, disappeared in the darkness of the night.

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Summary

“The Overcoat” by Nikolai Gogol is a literary masterpiece that blends elements of satire, social commentary, and existential exploration. Through the story of Akaky Akakievich Bashmachkin and his quest for dignity through a new overcoat, Gogol delves into the dehumanizing effects of bureaucracy and the profound impact of societal indifference. Here is an analysis of key themes and elements in “The Overcoat”:

- Bureaucracy and Dehumanization:

- Gogol satirizes the bureaucratic system and its dehumanizing influence on individuals. Akaky is a faceless clerk, reduced to a mere functionary in a vast bureaucratic machine. His existence revolves around mindless copying, highlighting the soul-crushing nature of his work and the anonymity imposed by the bureaucratic hierarchy.

- Quest for Dignity and Recognition:

- Akaky’s desire for a new overcoat serves as a symbolic quest for dignity and recognition in a society that often dismisses individuals like him. The overcoat becomes more than a garment; it represents his aspirations for warmth, comfort, and social acknowledgment. Gogol explores the universal theme of the human need for identity and respect.

- Social Injustice and Ridicule:

- The story highlights the cruelty of societal indifference through the ridicule and mockery that Akaky faces after acquiring his new overcoat. His colleagues and superiors, instead of empathizing with his modest achievement, mock him mercilessly. This underscores Gogol’s commentary on the callousness of a society that perpetuates social hierarchies and fosters a lack of empathy.

- Absurdity and Satire:

- Gogol employs absurdity and satire to emphasize the irrationality of the bureaucratic world. The absurdity reaches its peak when Akaky’s ghost seeks revenge by taking the overcoat of a high-ranking official. This surreal turn of events underscores the story’s satirical critique of societal injustices and the arbitrary nature of retribution.

- Existential Themes:

- “The Overcoat” explores existential themes, particularly the search for meaning and significance in a seemingly indifferent universe. Akaky’s quest for a new overcoat becomes a metaphor for the human desire to transcend the mundane and find purpose. The story reflects existential concerns about the individual’s place in society and the quest for personal significance.

- Irony and Tragedy:

- Gogol employs irony to accentuate the tragic aspects of Akaky’s story. The very overcoat that symbolizes his quest for dignity becomes the catalyst for his downfall when he is robbed and left to suffer in the cold. The ironic twists in the narrative contribute to its poignancy, showcasing the tragicomedy inherent in Akaky’s life.

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Theme

- Bureaucratic Dehumanization:

- One of the central themes is the dehumanizing effect of bureaucracy on individuals. Akaky Akakievich Bashmachkin is a low-ranking government clerk whose existence is reduced to monotonous, mind-numbing copying. Gogol critiques the impersonal nature of bureaucracy, emphasizing how it strips individuals of their humanity and reduces them to mere cogs in a vast administrative machine.

- The Search for Dignity:

- Akaky’s quest for a new overcoat becomes a symbol of the universal human desire for dignity and recognition. The overcoat represents more than a garment; it embodies Akaky’s aspirations for warmth, comfort, and social acknowledgment. Gogol explores how individuals, even in the most mundane circumstances, yearn for a sense of identity and respect in a society that often overlooks their existence.

- Societal Indifference:

- The narrative portrays the indifference and cruelty of society toward those on the margins. After Akaky acquires his new overcoat, he becomes the target of ridicule and mockery from his colleagues and superiors. This theme underscores Gogol’s critique of a society that perpetuates social hierarchies, fosters callousness, and lacks empathy for the struggles of its less privileged members.

- Irony and Absurdity:

- Irony and absurdity are pervasive themes in the story. Gogol employs irony to accentuate the tragic aspects of Akaky’s life, especially the ironic twists related to the overcoat. The absurdity of bureaucratic processes, social interactions, and Akaky’s ghost seeking revenge adds a layer of satire, highlighting the irrational and often comical aspects of human existence.

- Existential Isolation:

- Akaky’s existential isolation is a recurring theme. Despite his presence in a bustling city, he remains socially isolated and disconnected. Gogol explores the existential loneliness that arises from a lack of meaningful connections and the isolation that individuals may experience within a society driven by impersonal institutions.

- Symbolism of Possessions:

- The story uses possessions, particularly the overcoat, as powerful symbols. The overcoat symbolizes social status, personal identity, and the hope for a better life. Its loss and the subsequent decline of Akaky’s life underscore the story’s exploration of the profound impact that seemingly insignificant possessions can have on an individual’s sense of self.

- Social Critique:

- “The Overcoat” serves as a broader social critique, challenging societal structures and norms. Gogol’s narrative sheds light on the arbitrary nature of social distinctions, the absurdities within bureaucratic systems, and the consequences of a society that values materialism over compassion.

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Irony

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Short story – Full Text – PDF

Are you looking for a free downloadable PDF copy of The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol Full Text – PDF

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Analysis – PDF

Are you looking for the analysis PDF copy of The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Analysis

The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol – Theme – PDF

Are you looking for the PDF copy of theme around The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol? You’re in luck and look no further! You can download a free PDF copy right below.